So it turns out that recovering from post viral fatigue has been way more difficult than I originally anticipated. Like all the best journeys, the road has had moments of joy, despair and plenty of lessons in life and self. It may be a cliché, but I have learnt a lot through 2018. It is a while since I last wrote on this subject and I can now look back and see a number of distinct phases during the year.

In the mire

My previous blog on fatigue sets out how I ended up in this mess, but I guess it is summed up by living a fantastic yet crazy life and then not stopping soon enough when I got ill during the bad virus and flu season of the 2017-18 winter. When you have never been seriously ill in your life before it is all too easy to think you are bullet proof and you can just keep on carrying on. After all that is what you have always done.

Waiting it out

After all the wheels fell off the bus, I was initially confident that all I had to do was wait and rest. Given time, my body would recover and I just needed to learn to relax and wait it out. But after about six weeks it became clear that this illness was not going to go away quickly. Yet still I was sure that another month or so would sort everything out. Back in February and March I had no inkling that I would actually need nine or ten months and several changes of strategy.

Riding the roller-coaster

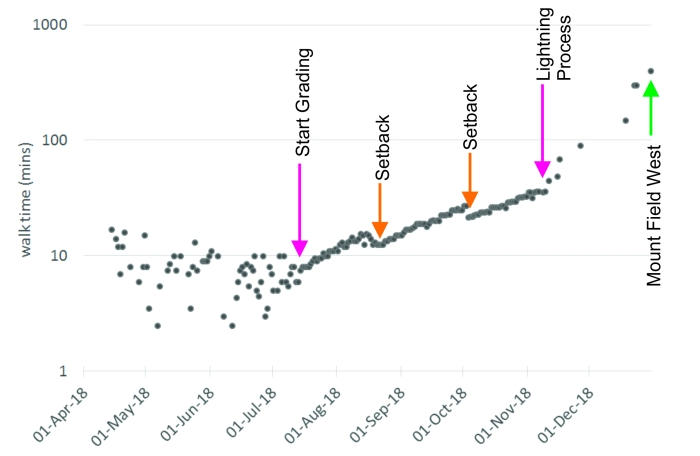

A characteristic of fatigue illnesses is boom and bust conditions: on good days you tend to do more and then pay for it later. Either immediately or delayed by one, two or even three days. For me this was more a saw tooth progression. A tendency to take two steps forward and one step backwards. When you don’t feel the impact of overdoing it immediately it can be hard to judge your activity levels. But that is what I had to do. It felt like walking a tightrope between overdoing it and not progressing at all. And getting this right was the key to starting to get better in a more systematic way. Because only when I stabilised the boom and bust did things go forward properly.

The mind and the body

Yet stabilising is so much more easily said than done. At the end of March / early April I had my first major setback which sent me spiralling into an emotional hole. When you have a good week, and feel like the beginning of the end of your illness is coming, the crash that follows is especially hard to bear. I found myself worrying about everything. Worrying about doing things in case it made me worse, worrying about never getting better. There were some dark days filled with anxiety and fear for the future. But I also saw how these negative emotions were taking me down. We all know mental well-being effects physical health, but when you have so little energy reserves, it is strikingly clear how draining stress and worry can be.

Striving to be happy and accepting my situation made a big difference to how things went. It was hard to maintain this positivity all the time, especially when you end up going down the saw tooth of a setback occasionally, but it became easier as time went on. However, I was later to come to understand that positivity was not enough: my fears were much deeper seated than I realised at this point and ultimately the route to recovery was to firmly quash them.

The occupational therapy approach

As the summer came round my referral to the Yorkshire Fatigue Clinic kicked in and I finally got some professional help. NICE regulations mean you have to wait four months to get a Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) diagnosis from your GP and then there are further waits to get an appointment. But once this process finally got going it was very helpful. After assessment the clinic re-diagnosed me with Post Viral Fatigue: I may have felt chronically ill, but apparently I was neither a severe enough case, nor long enough ill to be classed as chronic. Anna, the occupational therapist I saw at the clinic was great and a superb listener. She set me on the path of “pacing and grading”. Pacing to make sure you didn’t over do it, to minimise the chance of crashing and grading to gradually increase your activity in a controlled and phased way.

A new confidence

As the fatigue had totally destroyed my confidence, I found that grading my activity made a huge difference. Before I had been gradually increasing my activity overall, but in a haphazard way. On any given day I did what I felt up to. This could be more or less, but I had no certainty about what I could do and some anxiety about what I couldn’t thrown in for good measure. By grading – essentially very carefully controlling what I did, repeating it for 5 to 7 days and then increasing by 10% – I developed a new confidence about what I could do. And with this confidence I felt suddenly much better overall too.

What is often called “graded exercise theory” is controversial in CFS/ME circles. Recent research suggests that it makes many patients worse, but for me it was a massive help. And it was certainly not just about exercise, it was about applying the grading principles to every type of activity. Looking back I can see it was all about confidence and belief rather than increasing tolerance to exercise and activity in itself. Fatigue is a dysfunction of the autonomous nervous system, which controls your stress response or “flight and fight” response. When you have fatigue this stress response is getting triggered all the time, by the most minor of things, for examples just leaving the house. This stress response is the cause of all the fatigue symptoms: like exhaustion, muscle tension/pain, gut dysfunction etc. By increasing my confidence about what I could do, my stress response was getting triggered less frequently and hence my symptoms were gradually reducing.

However, while grading had initially really helped me, showing me what I could do, after a while it also began to limit me. Grading draws clear boundaries about what you can’t do as well as what you can. And this in turn fed my anxieties about being ill. It was time to move on to a different approach.

A year in maximum walking duration, and the impact of different strategies

Fear as the perpetuator

As the year moved into autumn the mind-body and body-mind links in fatigue became ever move apparent as my understanding of my situation deepened significantly. I came to realise that I had developed a perfectly reasonable, yet deep seated fear of doing things. Because I believed that if I over did it then I would make my symptoms worse and potentially have a major setback or relapse. This fear of making myself worse was constraining my recovery. Because those fears were feeding the stress response that drives the illness. My own thinking about the illness was causing it to perpetuate. While all the symptoms I felt were real physical effects, it became clear that the solution lay in the mind.

I started going to see a clinical physiologist to try and get a grip on my anxieties. We worked on what I was afraid of and tricks I could use to improve my relationships with my thoughts and fears. Most of these came from Acceptance and Commitment Theory (ACT) which proved a useful framework for fighting inner demons.

All this helped a lot, but as the year dragged on I was desperate for a further acceleration of progress. Everything was just going so slowly. I seemed to have spent the whole year in a cycle of thinking I couldn’t possibly still be ill by such and such a time, booking a holiday or other adventure and then having to cancel it. I was supposed to be going to Australia for Christmas and New Year and desperately didn’t want to pull out of yet another trip. What I needed was a step change.

The Lightning Process

I first heard about the Lightning Process in the summer from a friend. But the claims of rapid transformation of fatigue patients seemed too good to be true. It was hard to find out information about what was really involved in the three half-day intensive course, and with most of the sales pitch drawing on amazing recovery stories rather than data from clinical trials, it all made me naturally sceptical. As far as I could tell the approach was based on Neuro-linguistic Programming (NLP). But when I used my academic access to look up the systematic reviews for NLP I found there was no net benefit reported. To be honest it felt like some kind of cult. Most of the training was offered by evangelists who had been themselves cured. I couldn’t help but feel that in the void where many CFS/ME patients had been let down by the medical profession, that the purveyors of the Lightning Process sounded like they were selling snake oil.

How wrong I was.

As the autumn progressed and I started to understand how fear was perpetuating my illness I came to realise that I was actually in agreement with the underlying principles of the Lightning Process – that you have learned to be extremely good at being ill; that the expectation of activity worsening your symptoms leads to a pavlovian response; and that the only way out was to change your thoughts and retrain your brain. Essentially you need to use neuro-plasticity to change the default response of your brain. To do this you need to change your beliefs, to stop believing you are ill and that any activity is a threat to your health.

I looked into the Lightning Process more seriously. My main concern was that just attending the course was way beyond my current activity levels and could cause me to relapse. I looked at the ME association patient survey statistics and it showed that the process was one of the most successful treatments, but also had a high incidence of making attendees worse. In the end I decided I just had to take the gamble. I was fed up of being ill and wanted my crazy life back.

Tasmania and beyond

I attended the Lightning Process in mid-November. That gave me 4.5 weeks after completion to recover enough to get to Australia. It was a caving expedition to Tasmania with many good friends, but I would be happy just to attend and be away on holiday for the first time in 12 months.

The course had an immediate impact. The day after completing it, Pete took the day off work and drove me to the Yorkshire Dales. We went for a short walk and had lunch out. Prior to attending the course I hadn’t been out of the house for more than 2.5 hours in over 9 months. Now we had been out for more than double that, and I suffered no delayed fatigue response. Within a week I was walking up the smallest fells in the Lake District. Then I started driving again, just round York initially, and practicing getting public transport ready for the trip down under. By the time we left for the airport in mid-December I had still only made it as far as Leeds, Sheffield and Settle by train, so Australia remained a massive step. But my motivation was strong: I really really wanted this to work.

First hill of the year, 17th November

We were flying from Birmingham and our train got as far as Doncaster before stopping irretrievably with smoke coming from the rear two carriages. As a recoveree from a stress related illness, the dash for a £165 taxi to the airport on a Friday night was not what the doctor ordered. But we made it and I arrived in Hobart a day and half later in a state of total sleep deprived exhaustion. The second long haul flight in particular had contained a number of dark moments where I doubted myself and wondered if I had just made a humongous mistake. But the trick was to rationalise to myself that this tiredness was not a threat to my health but was totally normal for such a long journey across so many time zones.

Within a few days I was feeling better and working on my lost fitness. Over the following two weeks I built myself up to a solo ascent of Mount Field West. A walk of 17km (return trip) with 750m of ascent that took me almost 7 hours. I may not have got underground but being back in the hills had never felt so good.

Mount Field West summit, Tasmania, 30th December.

In retrospect, getting away was the best thing I could have done. Transplanting myself to a different environment with a load of expedition friends had the effect of ripping up the illness anchors of 2018, and replacing them with my old way of life. It was like coming home, despite being over 10,000 miles away.

Now 2019 has started and the challenges of 2018 are mostly left behind. I am planning plenty of personal and professional adventures. Despite a total of 9.5 months off work in the end, my hard labours in 2017 led to two major research funding awards during 2018, which I can’t wait to get my teeth into. There are invitations to go skiing, caving in the USA, and Indonesia and expeditions to plan. I am confident that 2019 is going to be a fantastic year.

2019 so far:

1000m of ascent on Mt Eliza in the South West Tasmania Wilderness. This area is sadly currently being ravaged by bushfires.

Kicking of my new research fellowship on energy geostructures with collaborators at the University of Melbourne (photo credit Yu Zhou, UoM)

Fatigue Resources:

Books that have helped me see things more clearly in 2018:

- Fighting Fatigue by Sue Pemberton at al. From an occupational therapy approach; I found this very helpful especially in the first half of my illness.

- CFS Unravelled by Dan Neuffer. Quite in depth, probably too much so in my opinion, but none the less good at explaining why an important part of the solution to CFS is in the brain.

- The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris. Explains ACT and how to use it to improve your relationship to negative thought patterns and hence improve your life. A useful self help book generally, but the tools it teaches are especially relevant for retraining your brain away from fatigue patterns.

- An Introduction to the Lightening Process by Phil Parker. To be honest, while the Lightening Process really did help me in a transformational way, I did not find this book that helpful at all. This is because the book is totally a sales pitch, and hence not suited to a professional sceptic like me. Plus, I had already bought into to the concepts behind the process. But, if you need convincing about the role of neuro-plasticity and the importance of the mind-body and body-mind links then you may find it useful. However, if you have a rather analytical mind then Dan Neuffer’s book may suit you better.

I am so pleased for you. Well done. I hope we can join you for some adventures in 2019.

Hi nice reading your poost